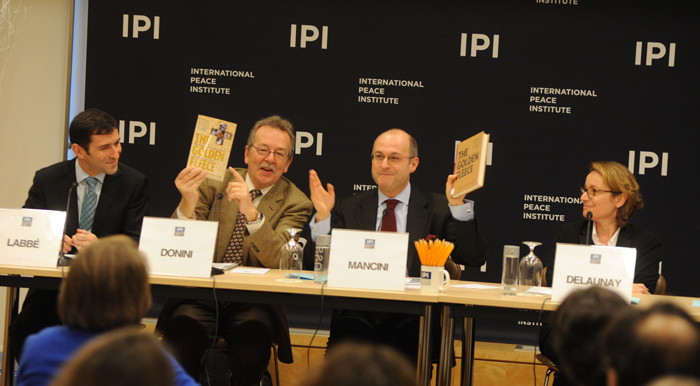

“One could argue that because the [humanitarian] enterprise has become so big and powerful, the stakes are now higher,” said Antonio Donini, Senior Researcher at the Feinstein International Center at Tufts University and editor of the book The Golden Fleece, at IPI’s Humanitarian Affairs Series February 11, 2013 event on, “The Elusive Quest for Principled Humanitarian Action: Past and Contemporary Challenges.”

“Humanitarianism itself, in a sense, has transitioned from being a powerful, ethical discourse to becoming itself a discourse of power,” he said.

“The humanitarian enterprise has seen massive growth and institutionalization over the past two to three decades. It now moves something like $15 billion a year [with] 250,000 aid workers,” he said.

Mr. Donini and Jérémie Labbé, Senior Policy Analyst at IPI and author of Rethinking Humanitarianism: Adapting to 21st Century Challenges, discussed both retrospective and prospective viewpoints on the state of humanitarianism. They were joined in the debate by Sophie Delaunay, Executive Director of Médecins Sans Frontières–USA (MSF), and Hansjoerg Strohmeyer, Chief of Policy Development and Studies Branch at the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), who brought the operational perspectives of their respective humanitarian organizations.

In addressing ideas raised in The Golden Fleece, Mr. Donini argued that there was never a golden era of humanitarian action. “The tensions between principles, pragmatism, and politics are nothing new; instrumentalization has always been there,” he said, projecting that the future of humanitarianism is becoming even messier and more complicated.

Mr. Donini went on to highlight the incorrigible issue of instrumentalization in humanitarian action relief, a problem in which relief is often hijacked in the name of achieving political or security agendas.

“The clash between the pragmatism of realpolitik and the ethical values that are at the core of the humanitarian message remain basically unresolved,” he stated.

Mr. Donini took the example of Afghanistan, where he spent many years. He asserted that the situation in the country was a good lesson of when principles are sacrificed on the “altar of politics.” Paradoxically, under the Taliban, there was a better sense of unity in the aid community on what was possible and what should not be done. However, after 9/11, the aid enterprise lost its moral compass as the humanitarian agenda was subordinated to political objectives.

Mr. Donini stated, “The disconnect between the functioning of a humanitarian establishment that is intent on reproducing and expanding itself and the daily reality of those it purports to help is growing.” In his view, the system of large aid agencies and donors remains self-referential, valuing growth over principle and effectiveness.

Mr. Donini asserted that while the current welfare structure is quite disjunct in the way it reaches people, it still continues to save countless lives and represents an ethos that cuts across cultures. The challenge is to figure out what humanitarianism will look like when other non-western traditions play a bigger role.

Delving deeper into the principles of humanitarian organizations, Jérémie Labbé explained the key fundamental areas the system needs to change: the universality of the undertaking, the relevance of the humanitarian principles, and the quest for increased coherence of the whole humanitarian endeavor.

“Today, clearly growing ambitions and changing modes of action of the international humanitarian system makes the respect for humanitarian principles ever more challenging,” Mr. Labbé said.

As the system increasingly tends to address the root causes of crisis rather than their effects only, Mr. Labbé stated that humanitarian actors should work “with communities and national authorities, to better prepare and ultimately strengthen the resilience of communities in the longer run so they can reconstruct better and more quickly.”

He went on to explain that this requires actors to work with and not around host states, to better link with development aid, and increase humanitarian aid with broader political objectives of good governance, peace and state building.

However, he pointed out, the constraints lie in how to reconcile this approach with the principles of impartiality, neutrality, humanity, and independence.

Mr. Labbé explained that the principles are not all equally important. “Humanity and impartiality are values that guide the humanitarian endeavor. Humanity means that the sole purpose of humanitarian action is to save lives and alleviate suffering, considering each life as sacred. Impartiality reflects the belief in the radical equality of each human life – aid should be delivered without any discrimination and according to one criterion only, the priority of needs,” he said. (Read Mr. Labbé’s interview on this topic in the Global Observatory).

“On the other hand, independence and neutrality are operational principles; they’re tools that make saving lives in an impartial manner possible, field-tested tools to guarantee security of staff, access to population in need by ensuring authorities that your action is independent of any military or political agenda,” he explained.

From his point of view, aid agencies should be more honest with their overall objectives and accept the limitations inherent to their choice. He asserted that humanitarian principles should be revisited and a more nuanced paradigm should be developed.

Bringing her field experience and operational perspective to the discussion, Sofie Delaunay of MSF -USA said, “Humanitarian actors need to accept a certain degree of instrumentalization if they want to operate because the space we get is a space we negotiate.”

She argued that humanitarian organizations need to acknowledge the risk of instrumentalization, citing the example of MSF’s experience in Misrata, Libya last year, in which they had to close down their medical program in a prison because they realized they were being used to treat detainees to be tortured again. The situation posed a tremendous dilemma to the organization, she said.

“I am convinced that instrumentalization will always be part of the humanitarian question, but the challenge for an aid organization like MSF, is clearly to define what is the acceptable degree,” she said.

Hansjoerg Strohmeyer said that when he started at OCHA in 2002, multilateral funding was at $1.9 billion. By contrast, he said the adjusted figures for 2012 were $8.9 billion.

In terms of the outlook of humanitarian action, Mr. Strohmeyer cited the recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2060 Global Growth Report, which said that while emerging countries and partners will grow, economic growth will not lead to less inequality, so overall challenges will increase.

“I don’t think there’s one humanitarian system. There is a multilateral system that has a multilateral framework,” he said, suggesting that the humanitarian coordination system needs to look to opportunities for increased cooperation.

The event was chaired by IPI Senior Director of Research, Francesco Mancini.

Watch event: