Organized crime and peacebuilding can be seen as separate issues, but recent research and practice suggest the two are deeply linked—conflict is increasingly fueling crime, and crime in turn makes peace harder to achieve.

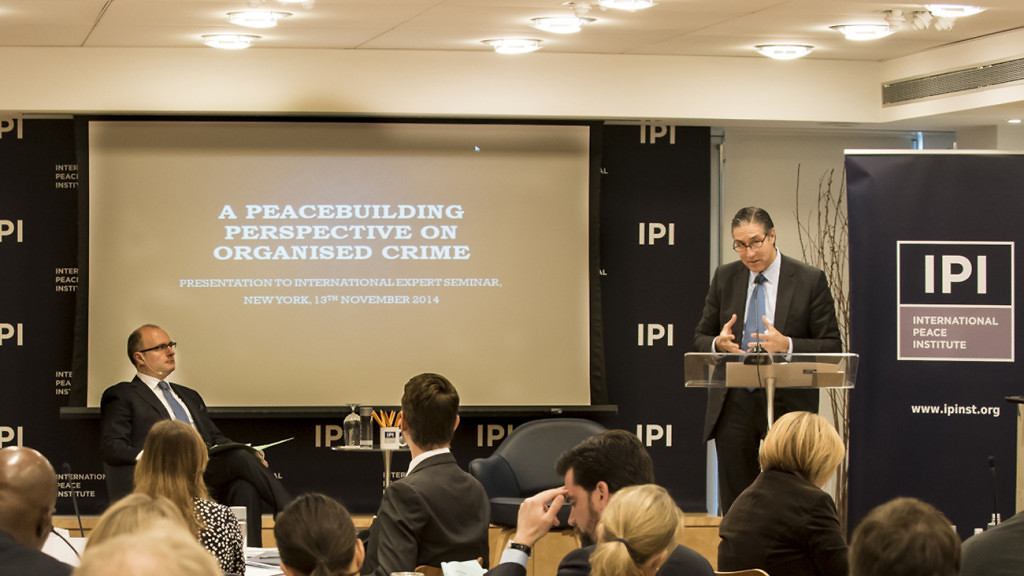

To address this phenomenon, IPI hosted a one-day workshop on November 13th on the topic of “Building Peace at the Nexus of Organized Crime, Conflict, and Extremism.” The event, co-sponsored by IPI, the Folke Bernadotte Academy, the SecDev Foundation, and the Center for International Peace Operations-ZIF, was the first of a series of seminars that will take place between 2014 and 2015 as part of the International Experts Forum—a gathering of experts, policy makers, practitioners, and academics who meet to discuss challenges to international peace.

The first seminar saw the participation of a large group of experts from a wide range of backgrounds, including the UN, the NGO community, and academia. The day-long discussion focused on the deep links between organized crime and peacebuilding in an effort to find ways to improve the work of peacebuilders around the world.

“In some way, crime has always been singled out on a separate shelf when it comes to security, governance, and development,” said IPI Non-resident Senior Adviser Francesco Mancini during opening remarks. “Actually, they are part of the same narrative.” The task, he emphasized, is to understand the nature of this link so that the international community can better face the growing challenges to stability.

Oscar Fernández-Taranco, the UN assistant secretary-general for Peacebuilding Support, delivered the keynote address and engaged in a lively conversation with the audience. Mr. Fernández-Taranco, who only recently took over as the head of the UN’s peacebuilding arm, stressed the need for a multidimensional approach to peacebuilding, one that goes beyond conventional ways and that can tackle the challenges posed by the spread of crime, terrorism, and extremism.

“Traditional instruments such as diplomacy or military means have not necessarily been that effective,” he said. Actually, he added, “military means alone to fight terrorism may have the adverse effects of feeding extremism.”

What is needed, he argued, is for the UN system to combine all its tools in order to create strong foundations for sustainable peace. “It’s about that joint and coherent effort, about common strategies of peacekeeping operations, special political missions, and UN country teams consisting of the agencies, funds, and programs.” If all these actors interact effectively, he added, the UN system can eventually reduce the risks of relapse into violence.

The UN official also noted that although peacebuilding is not the “magic bullet,” particularly useful are its emphasis on inclusivity and its focus on the extension of state authority. “Exclusion—political, social, economic—is one of the most consistent factors in the breakdown of peace,” he said, “and extremism is partly related to this marginalization of certain groups within countries.”

As for state authority, Mr. Fernández-Taranco said that when the state is absent or very weak, the vacuum that is created is dangerous because organized criminal groups can easily step in and fill it. “[They] thrive in those areas,” he lamented.

The seminar, which opened with welcoming remarks by Richard Zajac-Sannerholm, head of Rule of Law & acting research director at the Folke Bernadotte Academy, proceeded with a series of “ignite” presentations—brief TED-talk-like presentations. During the four interventions, the experts highlighted different angles of the linkages between peacebuilding and organized crime.

The videos below are of the four panelists presenting 10-minute “ignite” talks on topics about the links between peacebuilding and organized crime.

During her remarks, Jessie Banfield, an associate at International Alert, focused on the analytical tools to be used to understand the link between crime and peacebuilding. Looking at crime simply from a law enforcement perspective, she said, is limiting. Instead, we need to use the peacebuilding analytical framework with all its conflict-analysis tools. This way, she said, “we begin to open up a much broader spectrum of issues.”

James Cockayne, the head of the UN University Office at the United Nations, argued for a radical rethinking of the way crime is viewed in international relations. “[International relations] theorists tend to bracket off crime—they say that crime is distinct from politics because it pursues profits and not power,” he said. “That distinction,” he added, “is unhelpful and inaccurate.” Instead, he argued that there’s an intimate relationship between politics and organized crime. Citing recent research findings, Mr. Cockayne said governments have often relied on help from organized criminal groups for their operations, despite what many might think. Once we understand this, he said, we will understand that the problem requires a political solution.

The third speaker, Catalina Uribe Burcher of International IDEA, brought the discussion to the local level by focusing on the links between organized crime and peacebuilding in Latin America. In that region, she said, the problem of crime is particularly cumbersome for local law enforcement agencies because they lack the adequate resources to deal with it. In countries where people don’t trust their governments, criminal groups prosper thanks to the nature of their interconnected networks and to the fact that they operate at a local level where the state is absent. Stopping these illicit activities, she said, will require an active engagement with criminal groups at the local level. Ms. Uribe Burcher cited the ongoing negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC as an important example in that regard.

Finally, Naureen Chowdhury Fink of the Global Center on Cooperative Security focused her presentation on the links between peacebuilding and one type of organized crime in particular: violent extremism. “Violent extremism,” she said, “is both a product and a driver of conflict which calls for a greater integration of peacebuilding approaches.” Ms. Fink argued for a more integrated international response, noting how there is currently very little practical interaction between the counterterrorism and peace operations sides at the UN. This, she said, needs to change, and a starting point could be better coordination between capitals and the field, as well as a better communication strategy for the UN.

Watch event: