Diverse police forces that reflect the populations they serve are better prepared to carry out mandates for the prevention, detection and investigation of crime, the protection of persons and property, and the maintenance of public order and safety. As an illustration of that, in United Nations peace operations, women police have been challenging traditional gender roles and embodying a new model for independence, equality, and economic success.

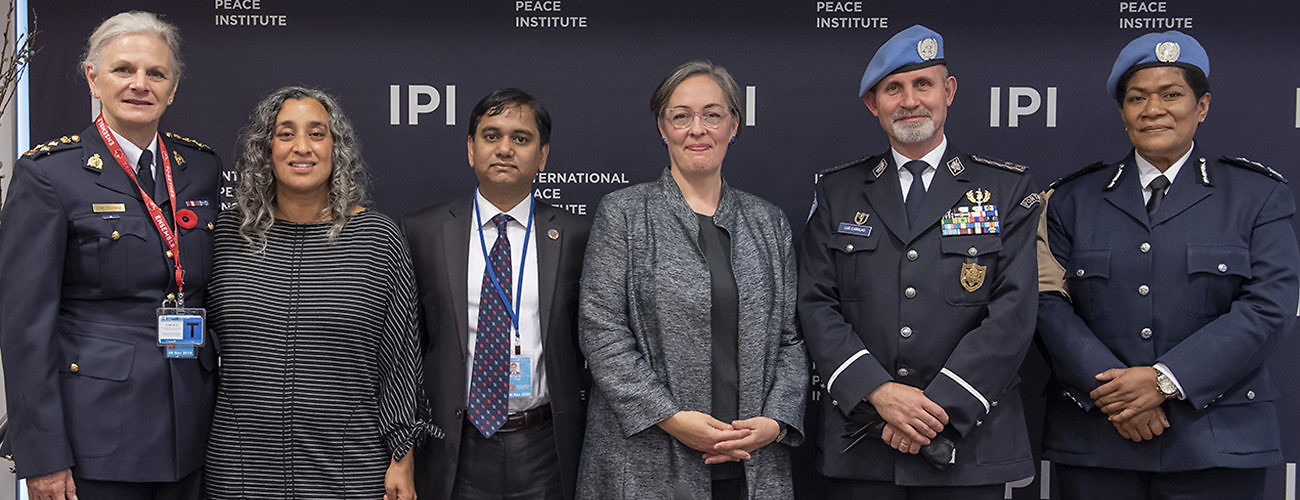

On November 5th, IPI, in partnership with the Government of Canada, Peace Is Loud, and the Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions in the UN Department of Peace Operations, hosted a discussion on experiences of women UN police (UNPOL) officers and how they contribute to implementing the women, peace, and security agenda.

The event began with a clip from the 2015 film A Journey of a Thousand Miles: Peacekeepers, which follows three women UNPOL officers in an all-female police unit deployed from Bangladesh to Haiti as UN peacekeepers for one year.

Geeta Gandbhir, the film’s director, showcased the experience of being on patrol with women, and the civilian response to seeing female police in place of male officers. Where people would often “hide” in their camps from the male troops, women and children came outside and followed the women through the camp, sometimes reaching to hold their hands. The women had “immediate rapport” with the community, she said. “This showed us how critical it was to have women on the ground.”

And the experience also had a positive effect on the women officers, she said, adding that it was a “powerful moment” seeing the women “transform.” The women in this unit came from patriarchal and fairly traditional families and had never enjoyed the independence and freedom of movement they suddenly encountered. Ms. Gandbhir said that one of the Bangladeshi police women told her, “We women go from our father’s house to our husband’s house.” In addition, women had mostly been assigned to desk jobs, and there was no opportunity for them to get field experience. “Some had never been on a plane,” emphasized Ms. Gandbhir, so “for them to travel to Haiti on this mission, alone, was an incredible act of bravery.”

These women also earned new financial security, Ms. Gandbhir explained, making on mission three times what women made in Bangladesh. And because they were able to pay for their children’s education, many women were willing to do additional tours, to be able to support their extended families as well.

Once the women returned home, they became a symbol of hope and emulation. One woman’s five-year-old son “told us that he wanted to be a big shot police officer, like his mother,” said Ms. Gandbhir. “To hear that statement alone told me that what the women were doing was smashing patriarchy and bringing equity and equality in both places where they existed—at home and abroad.”

Currently, of the 9,353 police personnel serving in 23 UN peace operations, 1,420 are women police officers. Luis Carrilho, a UN Police Adviser in Haiti who was featured in the documentary, told the IPI audience that gender parity was a “top priority” for UNPOL, and spoke about the UN’s efforts to make the police recruitment process more accessible. “Our strategy has goals in a very measured way,” said Mr. Carrilho. Regardless of whether the police troops were men or women, he reported, “The priority is always for us to fulfill the mission on the ground.”

Mr. Carrilho enumerated four initiatives that aimed to increase women’s participation in UN policing. The first, he said, was putting in place female role models, and gave the example of the female police peacekeeper of the year award. The next was creating a female senior police leadership roster which countries could draw on to place women in key positions. Third, he said, was developing a senior female police commanders course to better prepare female police to hold positions at the highest level. Finally, he added, was increasing the number of women involved in the selection process for peacekeeping.

Paula Dionne, Assistant Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, emphasized how “it is not enough to simply increase the number of females deployed. Rather, it is crucial to place them in key positions where the true value of what they do in conflict-torn states and countries can be realized.”

Policing and gender considerations have significantly changed in the past few decades, Ms. Dionne continued, citing her 33 years of experience. When she started, Ms. Dionne said, she had to wear a different uniform from the men and was “expected to take on pink jobs, as opposed to the tougher jobs.” Women, she said, had to “break down the barrier to our right to be part of specialized teams which were usually filled by males.”

Ms. Dionne concluded that “we have certainly come a long way in recognizing the value female police officers bring to peace and security, but there is more that can be done.” Necessary, for example, were “including a feminine voice in recruitment posters, a ‘she’ alongside the ‘he,’” attitude, which would entail adding photos of female officers to the material, and including female presenters at training sessions, which, “while seemingly small, goes a long way in encouraging female participation.”

Nirupam Dev Nath, Counsellor at the Permanent Mission of Bangladesh to the UN, said that the film “speaks volumes of the rewarding experiences” that, he said, “have long-term impact, not only in the host countries our women police officers serve in, but also globally, and back to their own country.”

Mr. Dev Nath pointed to the landmark UN Security Council Resolution 1325 in 2000, and how that was the first year that individual police officers from Bangladesh were sent to East Timor. Ten years later in 2010, the all-female police unit was sent to Haiti. Right now, he added, out of 700 police officers who are serving under the UN umbrella, almost 24 percent of them are women, which he hailed as a significant accomplishment.

The biggest challenges to deploying women peacekeepers, Mr. Dev Nath said, ranged from pre-deployment training down to including the family members in the decision making. In fact, he added, women’s participation in peacekeeping was felt deeply by the community; he called it an “inclusive journey” that bore “real fruit.”

Unaisi Vuniwaqa, Police Commissioner for the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), spoke on challenges to recruiting women for peacekeeping police, from her own experience. Access to opportunity, Ms. Vuniwaqa said, is “very key.” Prior experience, she argued, “will greatly help them when they come into the mission to be able to deliver at the highest level, whether it’s police commissioner or deputy police commissioner.” Without such exposure, said Ms. Vuniwaqa, it would limit being able to come into the mission and getting the opportunity to serve at a higher level. Additionally, she said, what was needed was more confidence in leaders who recruit and deploy police women, so that women are able to take on equal responsibility before they embark on the mission.

Ms. Vuniwaqa shared her personal experience of persisting in finding a place. “I had to try about three or four times to be able to get into the professional position in the police division,” she said. “I continued to look at myself in every attempt that I made and how best I could be able to package my CV and my experiences.”

Ms. Vuniwaqa attributed her ultimate success to a course benefiting female officers for UNPOL. This course, she said, helped her to prepare for further interviews that she was able to get through. As a result, she tried to replicate this course for recruitment in the South Sudan mission, “to assist our female officers to prepare the forms that they’re supposed to submit to a police division before they can then be listed for the interview.”

One of the telling stories from women police in her mission, concluded Ms. Vuniwaqa, was how they recently appointed two female officers for the position of POC coordinators. They are in charge of this protection of a civilian site in South Sudan that has about 30,000+ IDPs. “And since we put in these two female officers, they have been doing a great job,” she said. And “of course,” she added, “they can do just as well as their male counterparts.”