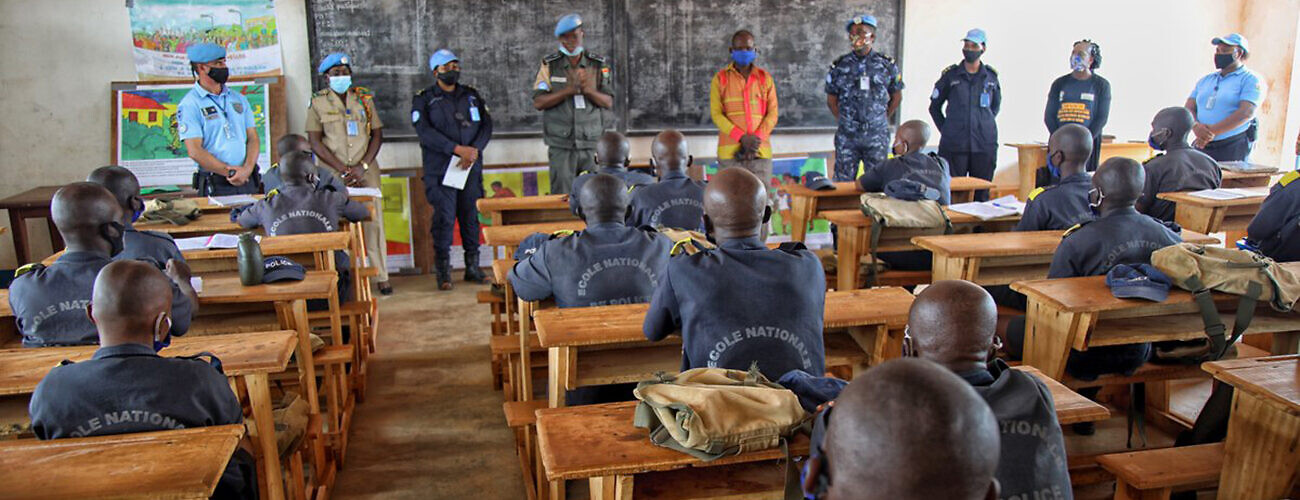

UN police in MINUSCA hold a training to equip local police academy students in the Central African Republic to prevent gender-based violence. August 7, 2020. (UN Photo)

Over the past decade and a half, specialized police teams (SPTs) have emerged as an innovative complement to individual police officers (IPOs) and formed police units (FPUs) in UN police peacekeeping. In general, SPTs are comprised of police officers and civilian policing experts focused on “skills transfer” and capacity building through technical assistance and advice, training, and mentoring to host-state police in a specific area of police operations or administration.

This paper provides an overview of the benefits and challenges of SPTs as compared to IPOs. Some of the benefits include that SPTs are generally highly capable and meet high standards in specialized areas of policing, provide a more coherent and cohesive approach, and focus on objectives within a specific area. They also maximize capabilities by matching the work of officers to their skill sets, can be quick to deploy and adaptable, and maintain continuity by implementing longer projects. Moreover, SPTs facilitate relationship building with host-state police, use sustainable capacity-building approaches such as training of trainers, provide broader benefits to missions, and are more attractive to some police-contributing countries.

At the same time, several obstacles to greater effectiveness have emerged, including that SPTs confront high-level tensions over their development and administration, experience supply-side issues due to their reliance on voluntary contributions and shortages of specially trained officers and civilian experts, and are dominated by countries in the Global North. They also have inconsistent composition, plans, and modalities across and even within missions and phases; lack sufficient guidance on key operational aspects; and lack consistent and sufficient funding. Moreover, SPTs are disconnected from broader efforts, sometimes implement unsustainable programming that focuses on “quick wins,” and often lack adequate frameworks for monitoring and evaluation.

The lessons emerging from the experience of SPTs to date emphasize the need for innovation around deployment and implementation modalities for this specialized approach to capacity building. At the same time, they highlight the need for greater organizational flexibility and adaptability to empower and maximize the potential of SPTs.